“This is what our fight looks like”

The European Wergeland Centre co-hosts Ukrainian Film Festival

By Veslemøy Maria Svartdal

When Ukrainske filmdager opened in Oslo, the European Wergeland Centre helped bring stories of schools under fire to the big screen — drawing attention to the resilience of Ukrainian teachers and the Centre’s decade-long support for democratic education reforms.

Ukrainian art and colours filled Cinemateket in downtown Oslo as Ukrainske filmdager, the annual festival celebrating Ukrainian cinema, opened its doors.

This year’s edition, “Maps of Time and Space,” presents films exploring Ukrainian everyday life, history, and emotional landscapes — shaped today by Russia’s ongoing war of aggression.

The festival was officially opened by Oslo Mayor Anne Lindboe, Ambassador of Ukraine to Norway Oleksiy Gavrysh, Acting Executive Director of the European Wergeland Centre, Ingrid Aspelund, and Project Coordinator for Ukrainske filmdager, Yulia Pidlisna.

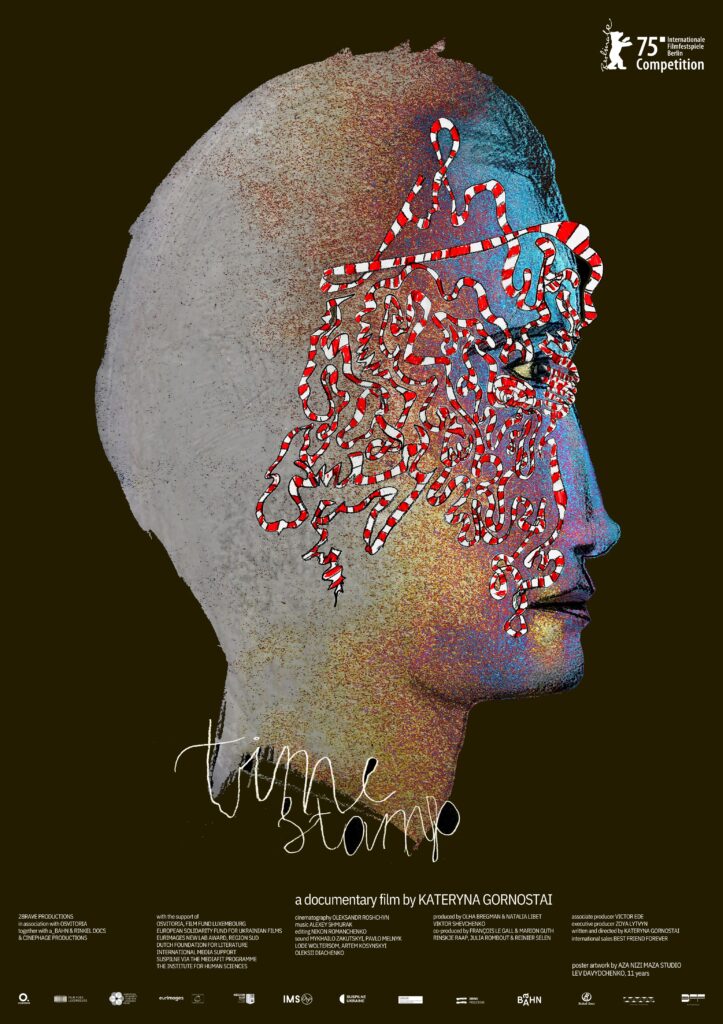

The opening film, Timestamp, directed by Kateryna Gornostai, sheds light on one of the less visible consequences of war: its impact on education. Rather than depicting frontline violence, the documentary follows teachers and students across Ukraine as they attempt to maintain school life amid air raid sirens, destroyed buildings, unspeakable loss and constant uncertainty.

Following the screening, Advisor at the Wergeland Centre, Anders Fedoryshyn Glette, moderated a conversation between Zhanna Dufina, Communications Advisor at Osvitoria – the film’s producer, and Ukrainian teacher Nataliia Gutaruk.

PHOTO: Taras Bezpalyi

“The film doesn’t show any violence directly, but the war is so intertwined in our lives that it is everywhere,” says Zhanna (middle). “We have a lot of footage from currently occupied territory or from territory close to the frontline. Our team chose not to include it because of safety reasons. It would be extremely unsafe for teachers and families there.”

Osvitoria, a non-profit organisation working on education reform since 2013, has had to adapt rapidly since Russia’s full-scale invasion. Alongside supporting teachers and students through learning platforms and professional networks, the organisation now engages in international advocacy to help sustain Ukraine’s education sector under attack.

PHOTO: Taras Bezpalyi

“We don’t believe it is a coincidence that so many educational institutions have been damaged during the war,” Zhanna says. Thousands of schools have been damaged or destroyed, forcing closures and limiting access to on-site education for hundreds of thousands of children.

“The priority is to bring children back into the classroom. With four years of war and two years of COVID-19, a whole generation of children has never been inside a classroom. That is very challenging,” she says.

Eight Metres Underground

Nataliia Gutaruk teaches at one of Ukraine’s “underground schools,” a concept born out of necessity during the war. Due to repeated attacks on civilian infrastructure, schools are increasingly being built below ground. Kharkiv Metro School, which opened in 2023 and is featured in the film, was the first of its kind. Since then, several dozens have followed.

“Our school was one of the first in Ukraine. It was very challenging, because people didn’t have any experience with underground schooling, and were sceptical. What about air circulation? What about the absence of natural light? But our team coped with it, and it became our victory. In Zaporizhzhya alone we have 15 such schools, with 12 more being built,” Natalia explains.

These schools provide a sense of safety and community, allowing parents to return to work and children to spend time together in a secure environment.

Still from the documentary “Timestamp”

“Our lessons are not usual lessons,” Natalia smiles. “Psychological support comes first. During the holidays, students would come in their pyjamas and bring cookies and games. We watched movies together. They of course had some lessons in math, history and Ukrainian, to help them cover the educational gaps, but there was also time for entertainment and relaxation.”

Like other teachers in Ukraine, her role has evolved to include psychological and emotional support. Despite the school’s dress code, Natalia often wears soft, fluffy sweaters because her students like to start the day with a hug.

In between airraid sirens and blackouts, the children in “Timestamp” find the time to laugh, play and celebrate.

“Children are children only once in their lifetime,” says Zhanna Dufina.

Still from the documentary “Timestamp”

“Their parents are often exhausted. That is why we as teachers need to help students stay positive and make them focus on the here and now. Education exists. Your dreams exist. We talk a lot about the future. The students joke that the teachers know more about them than they do,” she laughs.

Natalia became very happy when she recently saw the statistics over which universities her students would like to attend. They were all in Ukraine.

“They visited universities abroad, they saw, they compared, and understood that their efforts actually do matter, and chose to stay in Ukraine. That feels like a personal victory for us.”

“Timestamp” shows the importance of maintaining education, even during war. “Education helps save the life of the country. It should be a top-priority,” Zhanna belives.

PHOTO: Taras Bezpalyi

Resilience as a Choice

Teachers have become symbols of resilience in wartime Ukraine. Natalia believes that the Russian attacks aim to break that resilience by targeting civilian infrastructure, leaving communities without light or heat for hours.

Despite this, education has continued for millions of children.

“In 2022, we survived. In 2023, we stabilised and understood that we need to get school reforms going, teacher training going, development programmes going,” Zhanna explains.

“This is what Ukrainian children are going through,” said Ambassador of Ukraine to Norway Oleksiy Gavrysh, during the opening of the film festival.

Through its Schools for Democracy programme, the European Wergeland Centre supports these efforts by promoting inclusive and democratic education. The programme has adapted to include trauma awareness, psychological support, and stress management, offering teachers vital professional development and a sense of community and solidarity.

“Resilience should not be taken for granted. It is a choice. It is a kind of energy that can be supported or disappear from time to time,” Natalia says, adding that the support offered by international organisations have been key to prevent burn-out and exhaustion among Ukraine’s teachers.

Zhanna believes there are many countries all over the world that can draw painful, but important lessons from the fight to maintain education in Ukraine:

“The film not only show the grief and destruction, but also hope and that there are many things that can be done,” she says. “It is a chronicle of our struggle. This is what our fight looks like.”

Representatives of the European Wergeland Centre with Zhanna Dufina and Nataliia Gutaruk/PHOTO: Taras Bezpalyi

The film festival Ukrainske filmdager is supported by Fritt Ord and the Saving Bank Foundation.

The “Schools for Democracy” Programme is implemented by the European Wergeland Centre in cooperation with the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, Center of Education Initiatives (Lviv), Step by Step Foundation Ukraine (Kyiv), SavED (Kyiv) and Step by Step Moldova (Chisinau). The programme is funded by the Nansen Support Programme for Ukraine. The Nansen Programme belongs to the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD).