Moldova’s Schools at a Democratic Crossroads

Amid disinformation and foreign influence, Moldovan educators are shaping schools as spaces for critical thinking and democratic engagement

“Moldova’s democracy is still in transition, with complex challenges, but there is optimism thanks to the European integration process and international support,” says deputy principal and classroom teacher Svetlana Galben.

In June 2025, the European Wergeland Centre – in cooperation with the Step by Step Educational Program in Moldova – brought together a group of highly qualified teaching professionals in Chișinău for a three-day workshop.

One of them was Svetlana.

A Country in Transition

Moldova, one of Europe’s most economically disadvantaged nations, is undergoing rapid change. The country is grappling with accelerated price hikes, and spillover effects from Russia’s war against Ukraine, while also negotiating its EU future, having secured candidate status in 2022.

To address these issues and prepare for EU ascension, the Government of Moldova has agreed upon a long-term strategic vision: “European Moldova 2030”.

One of the key priorities outlined in the document is to foster a stronger civic consciousness among its population. This includes promoting youth participation in civic life and emphasizing values like tolerance, human rights, social cohesion and inclusion.

“Our project complements the reform efforts which are already taking place in Moldova,” explains trainer Marius Jitea, who led the seminar in Chișinău. “There is a lot of potential in Moldova. This country and others that are in various stages of getting closer to European values should be helped more and more.”

The Chișinău workshop launched the Wergeland Centre’s expanded Schools for Democracy programme, which from 2025 will not only support democratic school reforms in Ukraine, but also foster inclusive classrooms and participatory school governance in Moldova. The expansion was made possible by funding from the Nansen Support Programme for Ukraine.

This initiative is implemented together with the Step by Step Educational Program founded in Moldova in 1994. Executive Director Cornelia Cincilei, who has spent three decades advocating equal access to quality education and paving the way to learner-centred education in Moldova, looks forward to reaching 20 new schools this autumn and other 20 schools next autumn.

PHOTO: Cornelia in a green shirt (middle). Marius Jitea in a green shirt (right). Andriy Donets in black shirt (right).

“When it comes to the type of transformation that we are working with, there is no magic wand that will change your life from them outside. It’s a path, or a road. Change needs time. It is not just a one-time event,” she says.

Andriy Donets, the other trainer who worked together with Marius on the workshop, highlights the shared challenges across borders: “I believe that the ‘Schools for Democracy’ programme has opened paths that can be further supported and encouraged, paths that can be useful in Moldova. When I talk to teachers, it turns out that they struggle with a lot of the same issues as Ukrainian teachers – if you disregard the war, of course.”

Read also: The Ukrainian Success Story Continues

Senior Advisor at the Wergeland Centre, Marta Melnykevych-Chorna agrees:

“We want to expand and reach out to new countries. This is what the Wergeland Centre was created for – to promote education and human rights. Through the ‘Schools for Democracy’ programme, we have gained a lot of experience that we want to share with educators in Moldova. We will now work together with schools and support them through designing and carrying out projects that foster inclusive, democratic learning environments for everyone.”

Threats to Democracy

As Moldova prepares for parliamentary elections, Cornelia warns of growing disinformation and foreign influence campaigns.

“There is much frustration in Moldova about how things are not moving in the right direction, and it is difficult to counteract all of propaganda. The law of power overrides the law of justice, principles of coexistence and respect, and mere common sense. TikTok has become a big factor, and propaganda has become a weapon that is very hard to fight against, but we are trying our best to change this situation through education and our teachers,” she says.

Svetlana adds that Moldova’s education system faces multiple pressures: rising costs and stagnant salaries leading to teacher shortages; persistent urban–rural divides in infrastructure, technology, and teaching quality; low civic participation, particularly among youth; as well as external disinformation campaigns.

On September 22, Moldovan President Maia Sandu delivered an emergency broadcast, cautioning that Russia is attempting to destabilize the country through vote-buying, disinformation, and local collaborators — a threat to Moldova’s sovereignty and European future. She emphasized that if Moscow succeeds, Moldova could become a staging ground for attacks on Ukraine and risk losing its democratic freedoms.

“We live in a society where trust in state institutions is often low, and where citizens are regularly exposed to biased or manipulative media messages,” says fellow participant Lilia Calmîc. “This makes the task of educating a democratic society more challenging, but also more urgent. If students grow up in an environment where critical thinking and independent judgment are encouraged, they will be better prepared to resist misinformation and to participate constructively in civic life.”

Svetlana agrees: “A modern education system rooted in critical thinking and democratic values is one of the most powerful tools against manipulation, corruption, and democratic backsliding.”

FOTO: Sasha Pleshco/Unsplash

Building Inclusive Classrooms

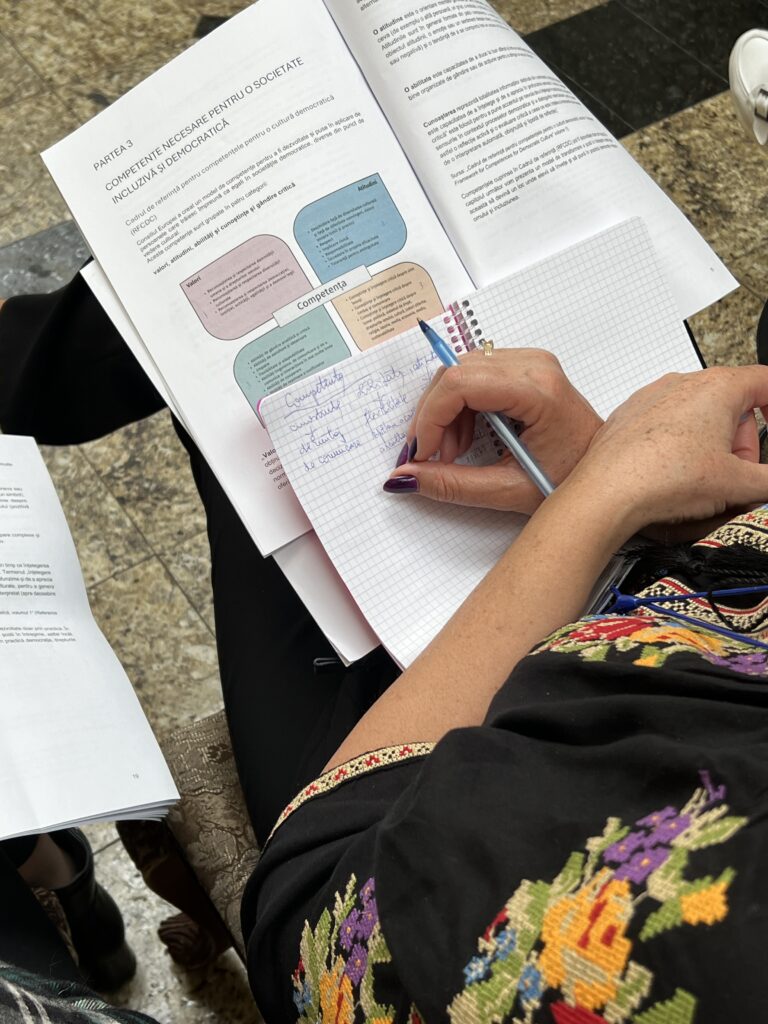

The training concentrated heavily on how to create safe, inclusive, and democratic learning environments – particularly for disadvantaged and vulnerable students.

Most participants were highly experienced teachers, many with backgrounds in working with marginalized communities. Cornelia praised the dedication of the teachers willing to challenge themselves and learn something new:

“They are open-minded, flexible, and willing to change themselves both professionally and personally. After a training session, our participants always say that their personal lives have changed too. They have become more resilient, more capable at problem-solving, and better at critical thinking.”

While participants were already familiar with many democratic education concepts through the Step by Step Educational Program, they sometimes struggled to put them into practice. The workshop offered practical tools to bridge this gap, preparing them to support schools as they make concrete steps towards inclusion in the coming academic year.

“That is the next step of this project,” explains Andriy. “Selected trainers will be asked to develop and conduct a three-day training for 20 participating schools from all parts of Moldova. Others will help develop teaching and learning materials and prepare webinars on topics relevant to the schools.”

Teachers as Democratic Role Models

Another major theme was the Whole School Approach, which emphasizes democratic practices in school governance and community engagement. For many participants, the idea of involving students, parents, local businesses, and authorities in decision-making was new.

“The participants were mainly concerned with students as part of the teaching process. They did not see how the community around the school can contribute, how local businesses can be involved, and how local authorities can be drawn in. Hearing that children should be consulted was new to many of them,” says Marius.

But for Lilia, this was already familiar practice:

“By supporting their involvement in volunteer projects, school initiatives, or social campaigns, we help the students see how their actions can have an impact, while also guiding them to take responsibility for the outcomes of their choices. Over time, these experiences build confidence, empathy, and a genuine interest in contributing to the well-being of their community,” she says.

“Like Sponges”

Though initially surprised that two male democracy trainers were leading a mostly female group, participants praised Marius and Andriy for their professionalism and the breadth of the course.

“The seminar was an inspiring and practical experience, highly relevant to my dual role as deputy principal and classroom teacher,” says Svetlana. “The topics—creating democratic and inclusive educational environments, democratic teaching methods, building community partnerships, cooperating with parents, and developing democratic school culture—are timely and essential. In the future, I will focus on involving students in decision-making, setting rules collectively, and promoting democratic learning and values-based education.”

Marius reflects on the energy in the room: “We broke through the language barrier, but I think we broke through many other barriers as well. The teachers were extremely open, extremely eager to learn, and engaged in everything that went on during the training. They were like sponges.”

The call for participating schools is now open, with a final deadline on October 3rd 2025.

The “Schools for Democracy” Programme is implemented by the European Wergeland Centre in cooperation with the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, Center of Education Initiatives (Lviv), Step by Step Foundation Ukraine (Kyiv), SavED (Kyiv) and Step by Step Moldova (Chisinau). The programme is funded by the Nansen Support Programme for Ukraine. The Nansen Programme belongs to the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD).