NORWAY: “Young People See Things Differently“

What happens when you let teenagers lead the conversation? After attending a democracy workshop on Utøya, young students brought democracy into the classroom.

By Veslemøy Maria Svartdal

“Why do you think we did this exercise?” Helma (15) asks.

At Fagerborg School in the centre of Oslo, class 9B is sitting in groups of four. Today, Helma is the one leading the lesson.

“These are things that happen all the time,” says her classmate Synne from her seat. “We have freedom of expression for a reason, but the question is what we use it for.”

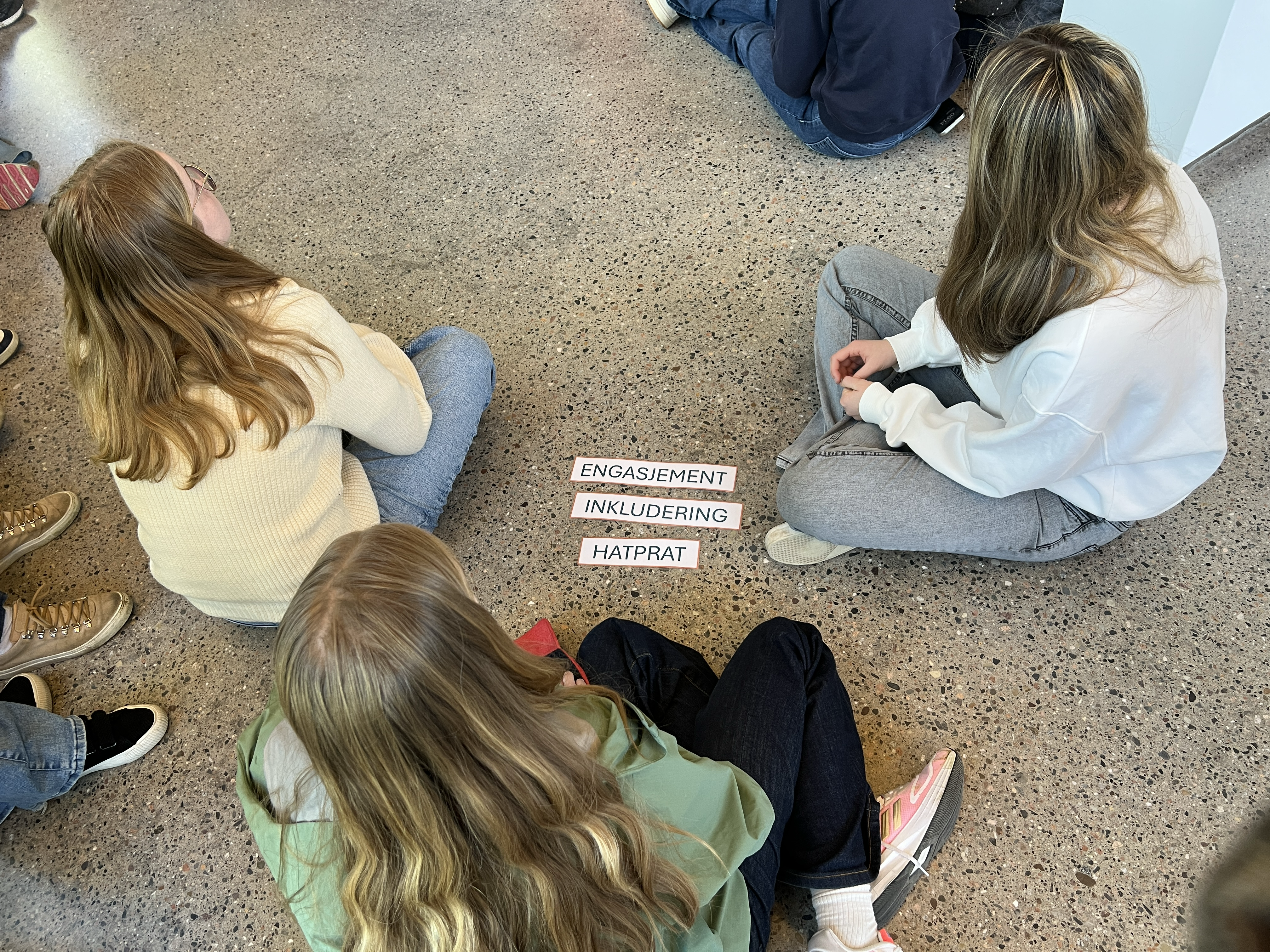

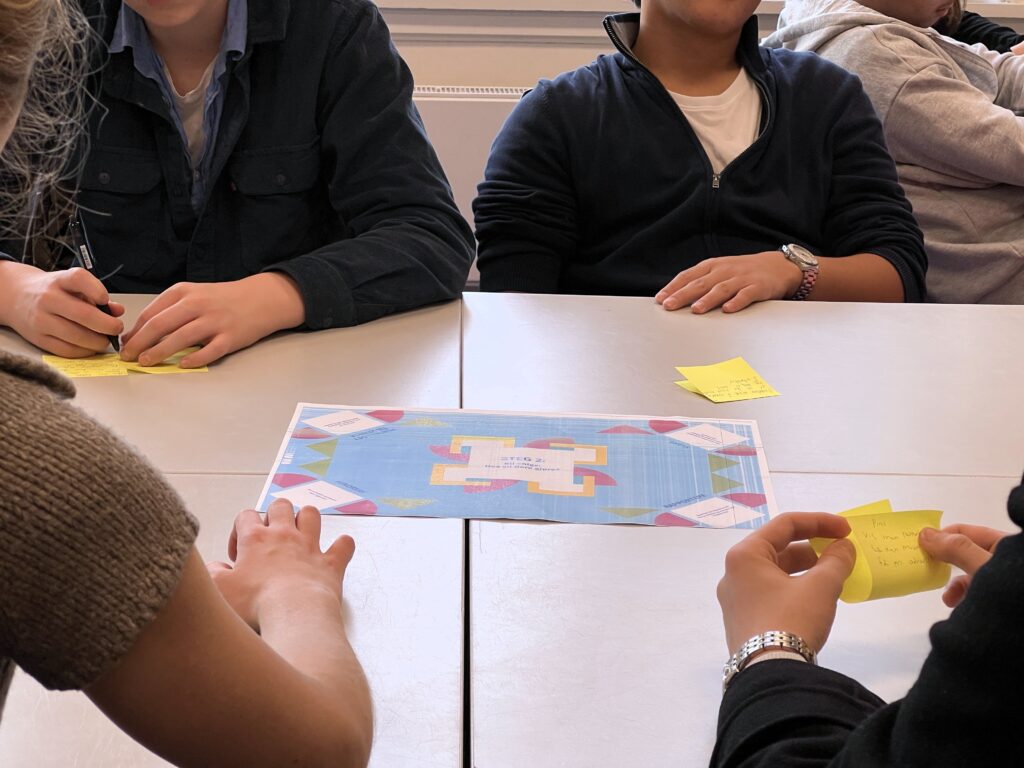

Class 9B has just completed ‘Dialogue Cloth: How to Respond to Hate Speech.’ The exercise challenges participants to reflect on what they would do if they heard someone make hateful comments at other people.

Helma, and two other girls from a parallel class, were first introduced to the exercise on Utøya, as part of ‘Democracy Workshop for Students and Teachers in 9th and 10th Grade’ — a free program for students and teachers from across Norway.

Young People Listen More to Young People

“Our philosophy is that young people listen to young people. When teens see peers who are active and care about democracy, they may feel that democracy is relevant for them too,” says Ida Berge, advisor at the European Wergeland Centre.

Ida and the Centre’s youth section have, in collaboration with the 22 July Centre, the Rafto Foundation, and Utøya AS, welcomed young people to Utøya for many years. The goal is to expand the concept of “democracy” to mean more than elections and voting rights, to show that young people are part of a democratic culture, and that they have the opportunity to influence local communities as active citizens.

In 2025, 280 students and teachers from schools across the country participated in the democracy workshop. Among them were Helma, her schoolmates Anna and Lilly (both 15), and teacher Gunnhilde Amundsen.

Students as a Resource

Gunnhilde had previously taken part in one of the teacher courses offered by the Wergeland Centre and the 22 July Center, which motivated her to return to Utøya and bring her students along.

“After attending the teacher course, I gained a larger resource bank and more ideas on how to approach teaching and tackle sensitive issues,” she says. “I also got to meet other teachers who experience the same classroom challenges as I do. Since society is constantly changing — and more so now than in a long time — I feel more secure having taken part in courses like this.”

The difference this time was that the students themselves, through targeted activities and reflection, developed belief in themselves as democratic citizens, and gained insight into activities they could present to their peers.

“I’m glad that the students themselves can become a resource — for the school, for my class, and also for me as a teacher,” says Gunnhilde.

22 July – Not Just History

The democracy workshop lasts three days and includes guided tours of the 22 July Centre and Utøya, where students learn more about the 2011 terror attacks, which costs the lives of 77 people. The students visiting Utøya today were barely born when the attacks took place.

“It happened when we were about one year old. We’ve only grown up with the stories and maybe memorial services. I probably feel less connected to it than the older generation,” says Anna.

For Gunnhilde, it is important that students do not see 22 July merely as a historical event like Kristallnacht or the sinking of the Blücher, but as motivation to engage in democracy:

“22 July is part of our society and not something that happened in isolation. We shouldn’t create fear, but rather motivate students to help prevent something similar from ever happening again,” she says.

New Concerns

On Utøya, the young people take part in various targeted activities that give them time and space to reflect, listen to others’ opinions, and understand different perspectives. One of these is ‘Engagement Cards’, where participants are asked to consider which issues in society concern them most.

The girls from Fagerborg were in no doubt about what mattered most to them:

“I’m most worried about climate change,” says Anna. “But it isn’t really a top issue anymore. I think we’ve gotten new things to worry about. Nuclear war, world war, democratic recession, COVID…”

“We’re influenced by what our parents say and what we hear in the news,” says Lilly. “I don’t think our futures will be very positive, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be completely horrible either. Maybe our generation — which has heard so much negativity — ends up fixing things.”

“It Means More When the Message Comes From Peers”

Before coming to Utøya, the girls felt they had little influence in politics, and that young people in general have limited power. It has been disheartening for many young people to see that the Fridays for Future climate strikes did not lead to major changes, they say.

It is important for the Wergeland Centre to build young people’s confidence in themselves as political actors, and their trust that positive change can happen within the democratic system — even if it isn’t always easy. On Utøya, young people get time to discuss issues and present their views to everyone.

Helma believes it means a lot to young people when the message comes from someone their own age:

“You might think you don’t have much influence and that you can’t achieve much on your own. But when you see someone your age with the same opportunities, you start to think you could do the same.”

“The reason why young people feel like they don’t have any influence, is because adults don’t give them the space,” Anna adds. “If adults talk to us about something, it won’t have the same impact as when a young person does.”

Harsh Language in the Schoolyard

Research shows that seven out of ten Norwegian school heads believe there is too much swearing and use of slurs in the schoolyard, and that this poses a threat to safe classroom environments.

It can also be a threat to democracy if certain groups in society do not dare to speak up out of fear of backlash.

“It can be a bit difficult to tell the difference between joking and reality,” Lilly said before participating in the democracy workshop. All three girls described a daily life where harsh language had become normalized.

Through ‘Dialogue Cloth: How to Respond to Hate Speech’ — which the girls also brought back to their school — participants learn what counts as hateful speech and how they can respond to it.

Gunnhilde also cares deeply about creating good classroom environments. Together with other teachers at the democracy workshop, she took part in observation rounds with students and in dedicated teacher activities that offer concrete advice on avoiding conflict in the classroom — especially when controversial topics are discussed.

“It can be challenging to let students say what they think, because I know what they say can be like dynamite for someone else. We have to talk about why we have freedom of expression and how important it is,” says Gunnhilde.

Speaking up – even when it’s difficult

The girls share that it was a bit nerve-wracking to stand in front of the class and lead discussions about freedom of expression, the foundations of democracy, and respect for other opinions.

“The first time was a bit chaotic because we didn’t quite know how to explain the activity. The second time went much better. We had more control, and more people understood what we were doing and why,” they say.

The democracy workshop gave them greater insight into issues related to extremism and hate speech, and they believe their classmates also gained a better understanding of how hateful utterances can appear in everyday life — and how and why one can respond.

The girls from Fagerborg say they have become more aware that democracy is fragile and must be protected. During the presentations, they noticed that not all classmates were aware of how Norwegian democracy is under pressure — making it all the more important to keep the conversation going.

“What’s nice is that young people often have a slightly different perspective. They can see things in another way. That’s really important for democracy — to get different perspectives,” Helma smiles.

The national learning program ‘22 July and Democratic Citizenship’ is funded by the Ministry of Education.