Navigating Uncertainty

Teaching Human Rights in Wartime Ukraine

By Veslemøy Maria Svartdal

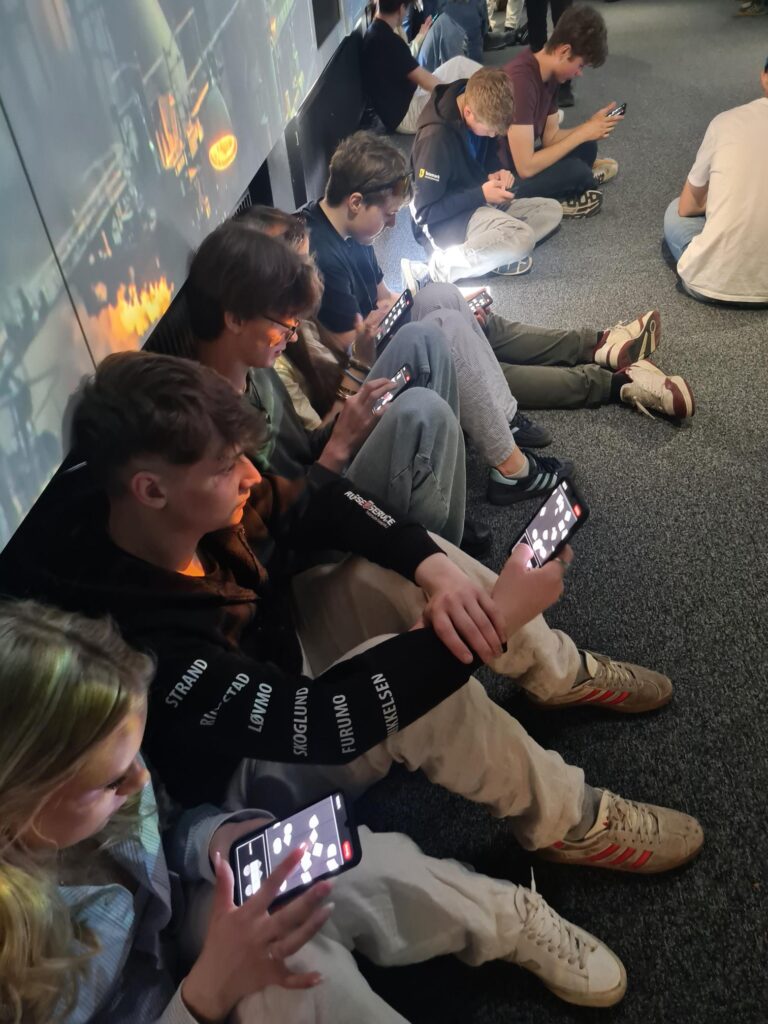

The battlefield in Ukraine can be found not only at the front, but also inside young peoples’ phones. Can human rights training help young people think critically and stay resilient in wartime?

A young person’s phone is a strange place. It feels like your own private universe – a digital world where only you make the rules. But in truth, it’s a wild frontier ruled by a shadow realm of algorithms and billionaires, shaping what you see, feel, and believe.

The world inside that glowing screen looks distorted, populated with people with more money, more things, more opportunities than you. They pop up between reports from the frontline, memorial videos of soldiers and crowdfunding drives. They don’t sleep in a hallway between the kitchen and the bedroom, or know what a Shahed drone sounds like. And if they do, it doesn’t look like it. “Outfit of the Day.” “Get Ready with Me.” Driving fast in a Lamborghini Revuelto. A lifestyle influencer on a yacht. “Habibi, come to Dubai!”

Then a message ticks into your DMs. “Do you want to make 5000 hryvnia? It’s easy. Just take a few pictures of a warehouse.”

A New Kind of Battle

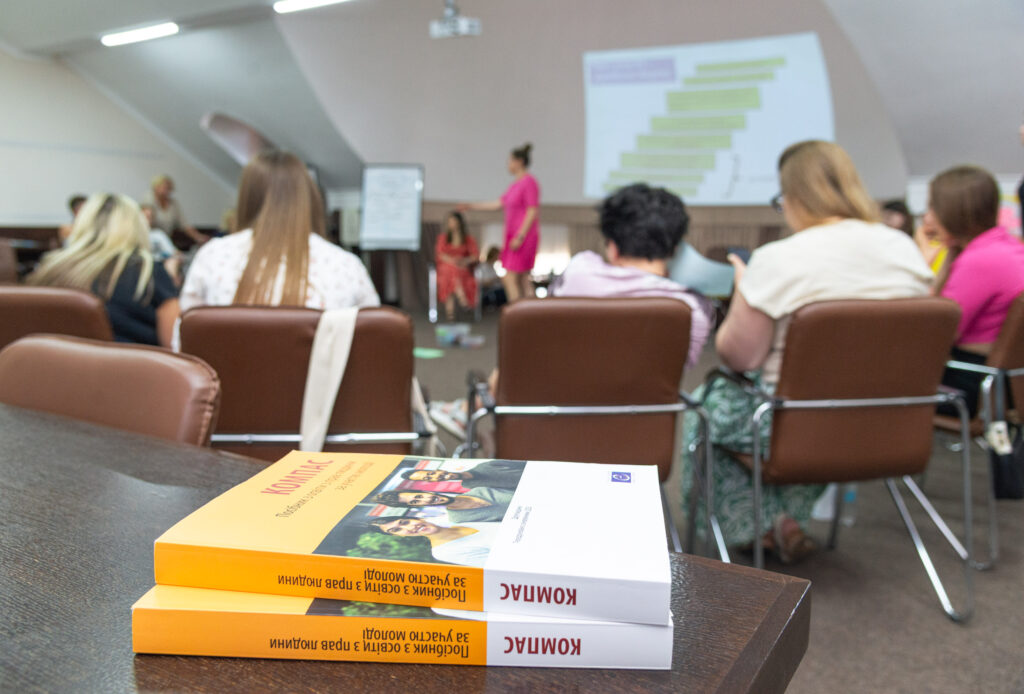

In the middle of a hot Lviv summer, 24 educators and youth workers of all ages got together to attend the European Wergeland Centre’s third annual Compass training. This year, a new topic was on the agenda.

“When we prepared for this year’s course, the Ministry of Education asked us to integrate radicalisation into our seminar programme. It is a new topic for Ukraine. We have never held trainings on this before,” says Olha Donets, Coordinator at the European Wergeland Centre.

She explains that recently, Russian secret services had begun to recruit Ukrainian youth to commit acts of sabotage against their own country in exchange for a few thousand hryvnias.

“We have had horrible cases of children being tricked by Russia,” says Anastasiia Konovalova, Ukraine’s Deputy Minister of Education and Science. “The children have damaged military vehicles or other objects – actually helping the enemy. It is not always easy. Teenagers’ job is to be difficult, and that makes it hard for us to help then when they have been the victims of disinformation.”

In times like this anyone could use a compass.

A Magical Tool

Compass is a Council of Europe educational resource for young people, supporting youth leaders, educators and civil society actors to integrate the knowledge and respect for human rights into the lives of young people. Its goal is to empower young people to become active citizens and defenders of democracy.

The seminar taught participants how to adapt Compass and other Council of Europe resources to local needs, showing how its exercises can be used across subjects — from history and literature to geography and even mathematics.

”We really believe that the Compass manual is a magical tool to integrate human rights education in schools and youth centres in Ukraine,” says Olha Donets. “The classic exercises do not cover the topic of radicalization. We adopted the exercise Take a Step Forward and discussed radicalization through push-factors and pull-factors.”

A Brief Respite

Since the pandemic and the Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the European Wergeland Centre has had to reduce the number of in-person seminars. The threat of airstrikes and the shortage of venues with bomb shelters make gatherings difficult.

The Compass training is a rare exception. Held in the western part of Ukraine, with a lower risk of airstrikes, participants from frontline counties found a brief, but welcome respite.

“For some participants it was their first time in Lviv. We had participants from Kharkiv, Sumy and Mykolaiv regions, where the security situation is very difficult. For them the seminar was not just a space to learn but also a place to relax,” explains Olha.

During the five-day seminar, the air alarm only went off once.

“We were very happy about that, because in Ukraine you can have the air alarm go off three or five times a day,” Olha says wryly.

In High Demand

The yearly Compass trainings are very popular. This year, the European Wergeland Centre received 500 applications from all over Ukraine.

Olha says it was difficult to choose from such a motivated and dedicated group of people.

With the youngest participant being only 19 and the oldest 65 years old, there were many cross-generational discussion and learning experiences enriching the seminar. Especially youth workers were surprised to learn how formal and informal education could work together to benefit the children in their local community.

Speaking to Vchysya Media, Olha Opanasenko, a youth specialist at the Nizhyn City Youth Centre, tells how the young people she works with are deeply engaged in shaping Ukraine’s future.

“Young people are interested in knowing how to communicate with local authorities so that they are heard, and how to implement certain projects at the local level. It is important for them to be involved in public life, not just for show. They really want to participate in various useful initiatives and contribute to changes in the community, and for this they need to know their rights,” she says.

Learning together

Following the training course in Lviv, various educational events on human rights has been held in schools and youth spaces throughout Ukraine. Students from the Merefa Gymnasium in Kharkiv Oblast and pupils from extracurricular institutions in Sumy Oblast learned how to cooperate, negotiate and defend human rights, while young teachers in Bila Tserkva in Kyiv region, sought together to discover their own ‘human rights superpowers’.

At the Merefa Gymnasium, students had just resumed in-person learning in a hybrid format, following an extended period of remote education prompted by the ongoing danger of Russian missile strikes.

“At first, the children were somewhat passive: not all of them wanted to move around or work in groups, and they were cautious in their interactions,” says participant Nataliya Bondarenko. “But at the end of the event, it was noticeable that the students had developed an interest in the topic, had become more confident, and were more willing to participate in the exercises.”

In Kegychivka in Kharkiv region, young people attended a discussion on freedom of speech and environmental responsibility. At a similar event in the Mykolaiv region, youth came together to talk about guidelines to prevent discrimination and promote tolerance.

“Young people actively participated in the exercises and discussed examples of discrimination at school and on social media. It was clear that the topic evoked strong emotions and interest. At the end, participants independently formulated rules for tolerant communication within their group,” says participant Olha Voituk about the event.

“The threat of radicalisation and the manipulation of children online by hostile actors is considerable, even in countries such as Norway, where children are tricked into breaking the law by criminal networks,” says Senior Advisor at the Wergeland Centre, Marta Melnykevych-Chorna.

“While I’m very impressed with what the participants have achieved once they returned to their local communities, I also see that they shied away from specifially using our exercise on radicalisation. This shows that educators need stronger support to address this challenge – and they cannot be expected to handle it alone. Combating radicalisation requires a whole society effort. It’s a difficult topic to discuss, but we must have the courage to engage with it.”

Compass training was implemented by the Center for Educational Initiatives (Lviv) and was funded by CoE and EWC through the Schools for Democracy Programme, which is part of the Nansen Support Programme for Ukraine.